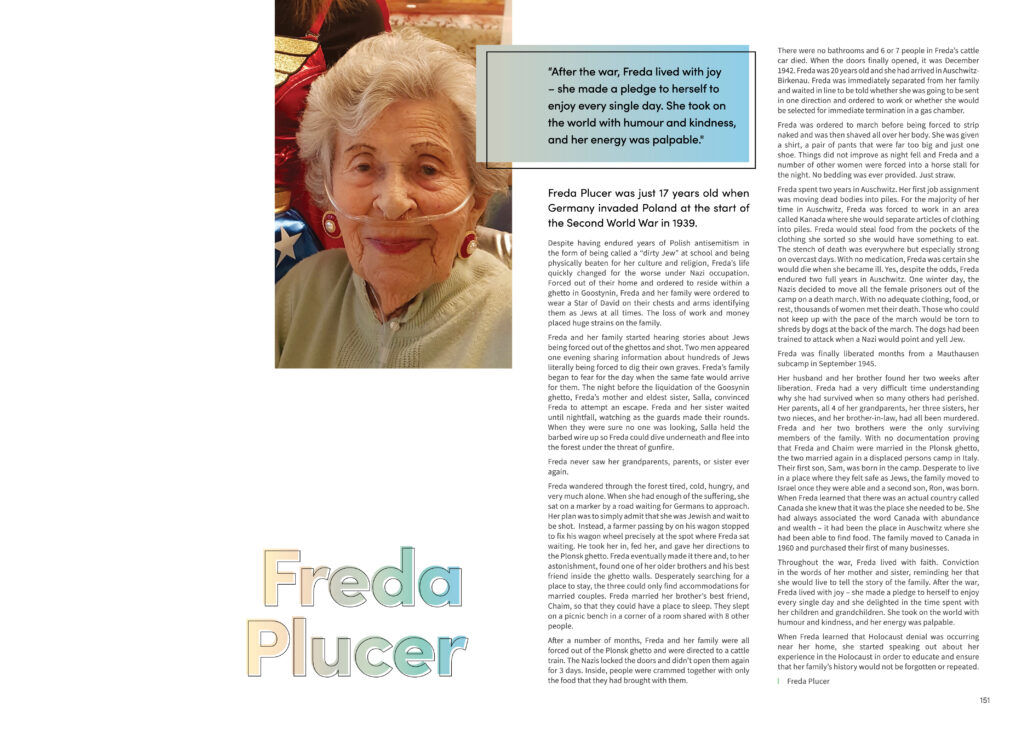

“After the war, Freda lived with joy – she made a pledge to herself to enjoy every single day. She took on the world with humour and kindness, and her energy was palpable.”

Freda Plucer was just 17 years old when Germany invaded Poland at the start of the Second World War in 1939. Despite having endured years of Polish antisemitism in the form of being called a “dirty Jew” at school and being physically beaten for her culture and religion, Freda’s life quickly changed for the worst under Nazi occupation. Forced out of their home and ordered to reside within a ghetto in Goostynin, Freda and her family were ordered to wear a Star of David on their chests and arms identifying them as Jews at all times. The loss of work and money placed huge strains on the family.

Freda and her family started hearing stories about Jews being forced out of the ghettos and shot. Two men appeared one evening sharing information about hundreds of Jews literally being forced to dig their own graves. Freda’s family began to fear for the day when the same fate would arrive for them. The night before the liquidation of the Goosynin ghetto, Freda’s mother and eldest sister, Salla, convinced Freda to attempt an escape. Freda and her sister waited until nightfall, watching as the guards made their rounds. When they were sure no one was looking, Salla held the barbed wire up so Freda could dive underneath and flee into the forest under the threat of gunfire.

Freda never saw her grandparents, parents, or sister ever again.

Freda wandered through the forest tired, cold, hungry, and very much alone. When she had enough of the suffering, she sat on a marker by a road waiting for Germans to approach. Her plan was to simply admit that she was Jewish and wait to be shot. Instead, a farmer passing by on his wagon stopped to fix his wagon wheel precisely at the spot where Freda sat waiting. He took her in, fed her, and gave her directions to the Plonsk ghetto. Freda eventually made it there and, to her astonishment, found one of her older brothers and his best friend inside the ghetto walls. Desperately searching for a place to stay, the three could only find accommodations for married couples. Freda married her brother’s best friend, Chaim, so that they could have a place to sleep. They slept on a picnic bench in a corner of a room shared with 8 other people.

After a number of months, Freda and her family were all forced out of the Plonsk ghetto and were directed to a cattle train. The Nazis locked the doors and didn’t open them again for 3 days. Inside, people were crammed together with only the food that they had brought with them. There were no bathrooms and 6 or 7 people in Freda’s cattle car died. When the doors finally opened, it was December 1942. Freda was 20 years old and she had arrived in Auschwitz-Birkenau. Freda was immediately separated from her family and waited in line to be told whether she was going to be sent in one direction and ordered to work or whether she would be selected for immediate termination in a gas chamber.

Freda was ordered to march before being forced to strip naked and was then shaved all over her body. She was given a shirt, a pair of pants that were far too big and just one shoe. Things did not improve as night fell and Freda and a number of other women were forced into a horse stall for the night. No bedding was ever provided. Just straw.

Freda spent two years in Auschwitz. Her first job assignment was moving dead bodies into piles. For the majority of her time in Auschwitz, Freda was forced to work in an area called Kanada where she would separate articles of clothing into piles. Freda would steal food from the pockets of the clothing she sorted so she would have something to eat. The stench of death was everywhere but especially strong on overcast days. With no medication, Freda was certain she would die when she became ill. Yes, despite the odds, Freda endured two full years in Auschwitz. One winter day, the Nazis decided to move all the female prisoners out of the camp on a death march. With no adequate clothing, food, or rest, thousands of women met their death. Those who could not keep up with the pace of the march would be torn to shreds by dogs at the back of the march. The dogs had been trained to attack when a Nazi would point and yell Jew.

Freda was finally liberated months from a Mauthausen subcamp in September 1945.

Her husband and her brother found her two weeks after liberation. Freda had a very difficult time understanding why she had survived when so many others had perished. Her parents, all 4 of her grandparents, her three sisters, her two nieces, and her brother-in-law, had all been murdered. Freda and her two brothers were the only surviving members of the family. With no documentation proving that Freda and Chaim were married in the Plonsk ghetto, the two married again in a displaced persons camp in Italy. Their first son, Sam, was born in the camp. Desperate to live in a place where they felt safe as Jews, the family moved to Israel once they were able and a second son, Ron, was born. When Freda learned that there was an actual country called Canada she knew that it was the place she needed to be. She had always associated the word Canada with abundance and wealth – it had been the place in Auschwitz where she had been able to find food. The family moved to Canada in 1960 and purchased their first of many businesses.

Throughout the war, Freda lived with faith. Conviction in the words of her

mother and sister, reminding her that she would live to tell the story of the

family. After the war, Freda lived with joy – she made a pledge to herself to

enjoy every single day and she delighted in the time spent with her children and grandchildren. She took on the world with humour and kindness, and her energy was palpable.

When Freda learned that Holocaust denial was occurring near her home, she started speaking out about her experience in the Holocaust in order to educate and ensure that her family’s history would not be forgotten or repeated.

Are you ready to share your story of RESILIENCE? You can do that HERE.