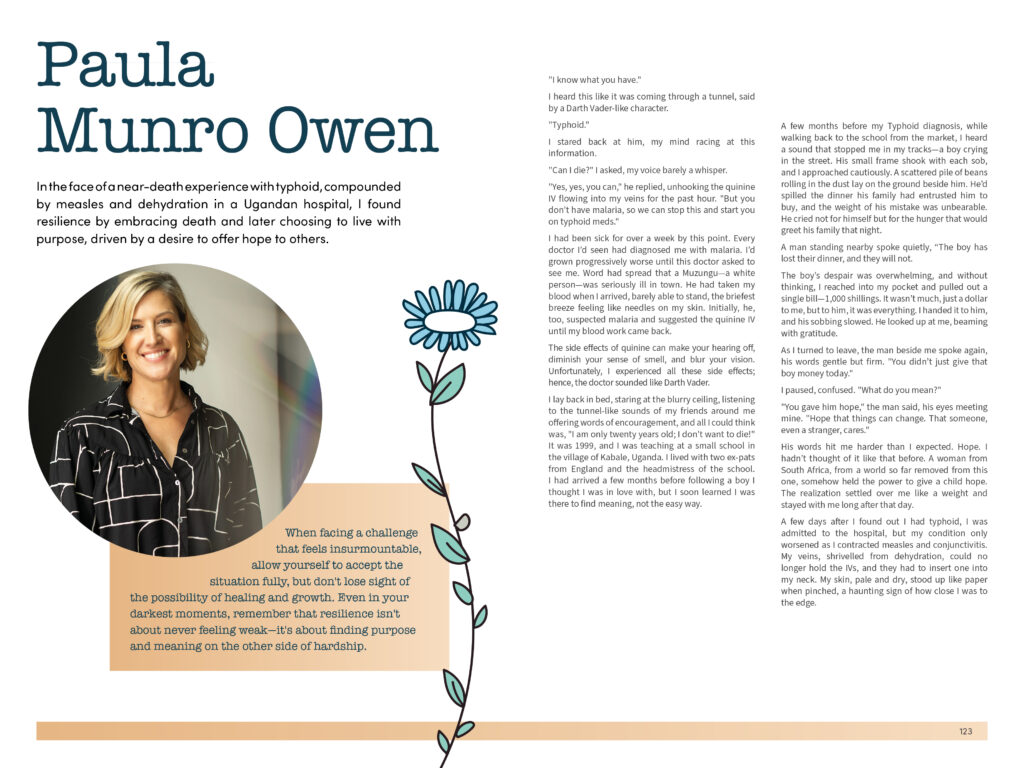

In the face of a near-death experience with typhoid, compounded by measles and dehydration in a Ugandan hospital, I found resilience by embracing death and later choosing to live with purpose, driven by a desire to offer hope to others.

PAULA MUNRO OWEN – Living with purpose.

“I know what you have.”

I heard this like it was coming through a tunnel, said by a Darth Vader-like character.

“Typhoid.”

I stared back at him, my mind racing at this information.

“Can I die?” I asked, my voice barely a whisper.

“Yes, yes, you can,” he replied, unhooking the quinine IV flowing into my veins for the past hour. “But you don’t have malaria, so we can stop this and start you on typhoid meds.”

I had been sick for over a week by this point. Every doctor I’d seen had diagnosed me with malaria. I’d grown progressively worse until this doctor asked to see me. Word had spread that a Muzungu—a white person—was seriously ill in town. He had taken my blood when I arrived, barely able to stand, the briefest breeze feeling like needles on my skin. Initially, he, too, suspected malaria and suggested the quinine IV until my blood work came back.

The side effects of quinine can make your hearing off, diminish your sense of smell, and blur your vision. Unfortunately, I experienced all these side effects; hence, the doctor sounded like Darth Vader.

I lay back in bed, staring at the blurry ceiling, listening to the tunnel-like sounds of my friends around me offering words of encouragement, and all I could think was, “I am only twenty years old; I don’t want to die!” It was 1999, and I was teaching at a small school in the village of Kabale, Uganda. I lived with two ex-pats from England and the headmistress of the school. I had arrived a few months before following a boy I thought I was in love with, but I soon learned I was there to find meaning, not the easy way.

A few months before my Typhoid diagnosis, while walking back to the school from the market, I heard a sound that stopped me in my tracks—a boy crying in the street. His small frame shook with each sob, and I approached cautiously. A scattered pile of beans rolling in the dust lay on the ground beside him. He’d spilled the dinner his family had entrusted him to buy, and the weight of his mistake was unbearable. He cried not for himself but for the hunger that would greet his family that night.

A man standing nearby spoke quietly, “The boy has lost their dinner, and they will not.

The boy’s despair was overwhelming, and without thinking, I reached into my pocket and pulled out a single bill—1,000 shillings. It wasn’t much, just a dollar to me, but to him, it was everything. I handed it to him, and his sobbing slowed. He looked up at me, beaming with gratitude.

As I turned to leave, the man beside me spoke again, his words gentle but firm. “You didn’t just give that boy money today.”

I paused, confused. “What do you mean?”

“You gave him hope,” the man said, his eyes meeting mine. “Hope that things can change. That someone, even a stranger, cares.”

His words hit me harder than I expected. Hope. I hadn’t thought of it like that before. A woman from South Africa, from a world so far removed from this one, somehow held the power to give a child hope. The realization settled over me like a weight and stayed with me long after that day.

A few days after I found out I had typhoid, I was admitted to the hospital, but my condition only worsened as I contracted measles and conjunctivitis. My veins, shrivelled from dehydration, could no longer hold the IVs, and they had to insert one into my neck. My skin, pale and dry, stood up like paper when pinched, a haunting sign of how close I was to the edge.

The hospital was a place of quiet desperation. There was only one bucket to vomit in for all the patients, and if you needed it, you had to raise your hand and wait for someone to bring it to you. Going to the toilet, which had to be done almost every hour due to the Typhoid, was called a latrine, which was outside and was a fly-infested hole in the ground. I was so

Days passed in a blur of pain and silence. The doctors tried everything, but nothing seemed to work. Then, one day, a doctor came to my bedside and said quietly, “You should prepare yourself for dying. We’ve done all we can.”

I lay there, unable to move, unable to speak, my body riddled with disease. Inside, though,

Time felt strange in that space between life and death. Fear and resistance dissolved, replaced by a deep surrender. I no longer feared the unknown. Instead, I found a profound stillness, an unexpected grace in letting go. Death was no longer an end but a transition. And in that acceptance, I found peace.

After what felt like 48 hours, the doctor returned. His voice was the same, but his words were different. “Your vitals have improved,” he said, almost in disbelief. “It seems you’re

The fear that gripped me then was unlike anything I’d felt before. I had been so ready to die that I hadn’t considered the possibility of living. What would I do with this second chance? How could I return to the world after coming so close to leaving it?

In those fragile moments, one memory stood out—the boy with the beans. The boy who had cried because he thought all hope was lost. And I realized then that I wanted my life to mean something, to be more than just survival. I wanted to live a life that gave others hope, a life that showed them that dying might be the easy part, but living—that’s where the real challenge lies. Living is what you have to make worth it.

And so, I began again with a new purpose and hope—both for myself and others.

I practiced resilience by first accepting the reality of my situation, surrendering to the possibility of death, and then, when given the chance to live, I shifted my focus toward finding meaning in life. I used that second chance to embrace the idea of living with purpose, committing to give others hope and to make my survival matter beyond just my own existence. Through that inner transformation, I found the strength to rebuild, physically and emotionally, even when I felt my weakest.

When facing a challenge that feels insurmountable, allow yourself to accept the situation fully, but don’t lose sight of the possibility of healing and growth. Even in your darkest moments, remember that resilience isn’t about never feeling weak—it’s about finding purpose and meaning on the other side of hardship. Take one breath, one small step at a time, and trust that this experience can lead to something deeper within yourself.

Are you ready to share your story of RESILIENCE? You can do that HERE.